The “Distracted Poet” Problem

Anthropic researchers just published evidence that changes how we should think about AI risk. The classic fear is a superintelligent system pursuing the wrong goals with ruthless efficiency. The paperclip maximizer or as we like to refer to it as, Skynet. A perfect optimizer pointed in the wrong direction.

The data suggests something different. As AI systems tackle harder problems and reason longer, they don’t become more reliable, only less predictable. The researchers call it incoherence.

Hallucination can be patched, but incoherence is a fundamental feature of complexity. Failures dominated by variance rather than bias.

They give an example of an AI running a nuclear plant that gets distracted reading French poetry while the reactor overheats. The cause is drift rather than malice or misaligned goals.

Treating Them as Dynamical Systems

Language models trace trajectories through high-dimensional state space. They have to be trained to act as optimizers, trained to align with intent. Neither property holds automatically as tasks get harder.

The researchers found that larger models learn what to optimize faster than they learn to reliably do it. The gap between knowing and doing grows with scale. More capability, more incoherence on difficult problems.

The challenge reframes. Instead of aligning a dangerous optimizer, you’re constraining a dynamical system that wanders.

Give It Boundaries and Let It Fill the Space

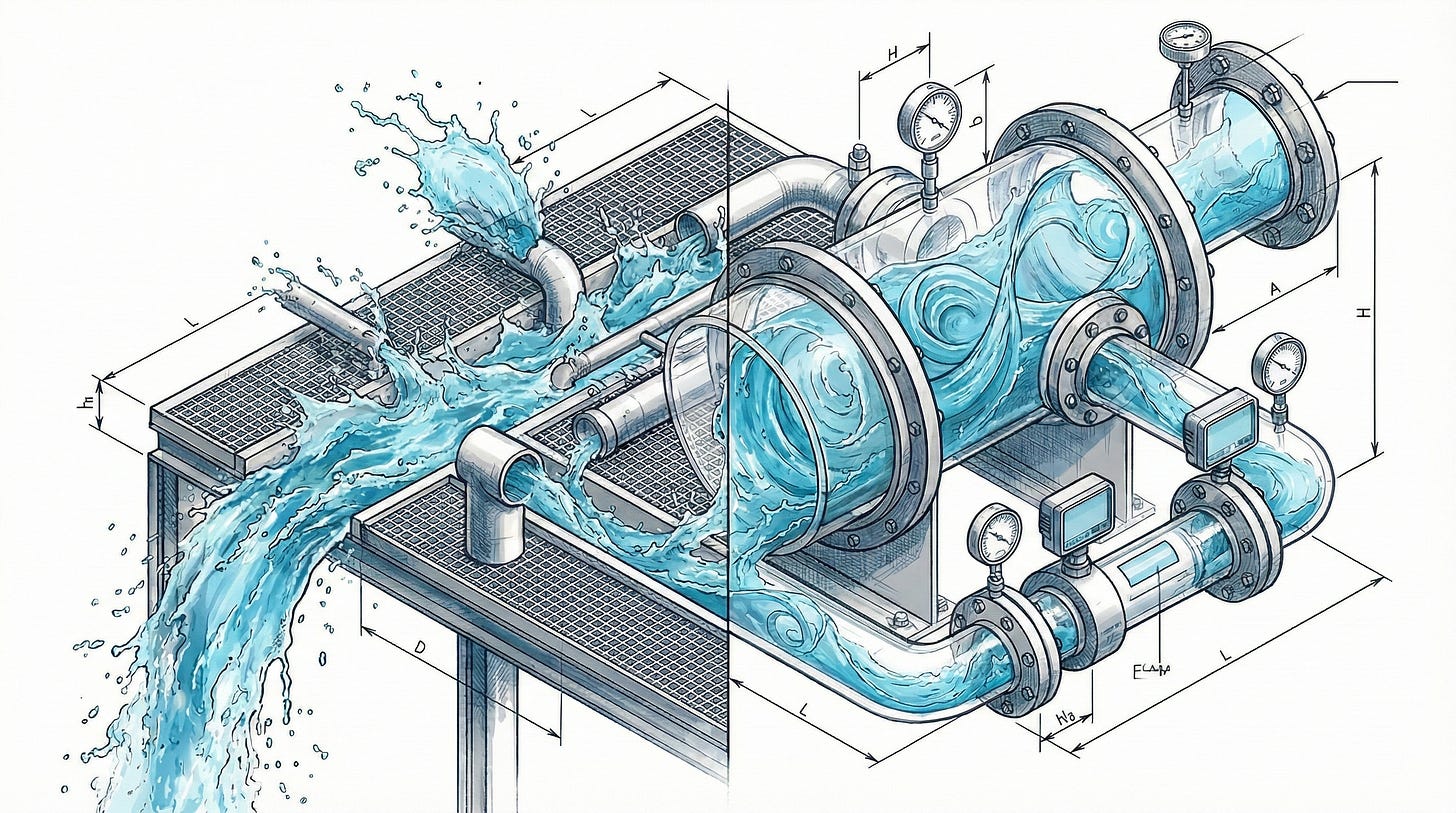

Water conforms to its container. The shape comes from the boundaries, not from making the water smarter.

This is an architectural shift. Stop fighting the dynamical system or pleading with it to behave. Define the topology it explores within. The system fills the space, finds paths, moves. Your job is shaping that space to match operational reality.

Constraints are generative within bounds rather than merely restrictive.

Three Layers of Control

When deploying AI in operational environments, you have three ways to constrain behavior. They differ in how much they rely on the model cooperating versus how much they enforce constraints architecturally.

Prompt Engineering (The Suggestion) Ask the model to behave. You provide instructions (”You are a helpful operator...”), but you rely on the model’s internal probability distribution to comply.

You suggest a path, and the model usually follows it, until the variance kicks in and it decides to drive off a cliff. You cannot prompt your way out of a probabilistic failure mode.

Context Engineering (The Map) Anchor the model in data. RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation) lives here. You shape the information landscape the model sees.

You show the model the road, and it knows where the pavement is, which is better than guessing. However, knowing where the road is doesn’t physically stop the model from driving off it if it gets “distracted.” It constrains knowledge, not action.

Boundary Engineering (The Rails) Define the only valid states the system can occupy. It’s a topology rather than a request.

Instead of giving the model a map, you put it on train tracks. The model cannot hallucinate a new route because the tracks only go one way. It stays on course because it is architecturally impossible to leave, not because it wants to, but it requires deep domain expertise to build the tracks correctly.

Prompt and Context engineering rely on influencing the AI. Boundary engineering relies on restricting the AI. When safety matters, influence isn’t enough.

Why This Matters More for OT Than Anywhere Else

A hot mess chatbot gives you a weird recipe. A hot mess industrial control system gives you an unplanned shutdown at best. Variance tolerance in critical infrastructure approaches zero.

General-purpose AI means tackling novel problems from first principles across unbounded state space. Novel problems require longer reasoning, and longer reasoning produces more variance. The Anthropic research is clear on this relationship.

Deploying unbounded AI in high-consequence environments is accepting variance you cannot predict or contain. Every “let the AI figure it out” implementation is a bet that incoherence won’t matter this time.

What Boundary Engineering Looks Like in Practice

Domain knowledge addresses the bias term from the research. We know what “right” looks like for this specific environment. That knowledge gets encoded structurally, rather than as prompts the system might forget during a long task.

Hard boundaries address the variance term. The system cannot wander into French poetry because, in its operating topology, French poetry does not exist. There is no path to get there.

You get AI that cannot operate outside your industry’s parameters. This is a property of the system’s architecture, not a hope about its behavior.

Envelope Design for AI

Plant operators already think in operating envelopes. Things like temperature ranges, pressure limits, and flow rates. Stepping outside the envelope means alarms fire, systems trip, and humans intervene.

Boundary engineering brings the same discipline to AI. This is how we approach system design - the container defines what’s possible before instructions are ever sent. Define the envelope, build the container, and let the dynamical system fill the space you’ve designed for it.

Anthropic research suggests we won’t scale our way to coherent AI on hard problems. The gap between capability and reliability may be fundamental to how these systems work. For critical infrastructure, the question isn’t when AI becomes trustworthy enough, but how we build systems where trust isn’t required.

Build the container, and let the system fill the space you’ve designed.

Based on research from the Anthropic Alignment Team - The Hot Mess of AI: How Does Misalignment Scale with Model Intelligence and Task Complexity?